MiCA in the Czech Republic After Six Months: Why Hasn’t the CNB Granted a Single License Yet?

On 18 December 2025, the Czech National Bank (CNB) published on its website a response to a freedom of information request concerning the number of (un)licensed entities in the crypto sector. The information(CNB Information Request Response) is valid as of the end of October 2025.

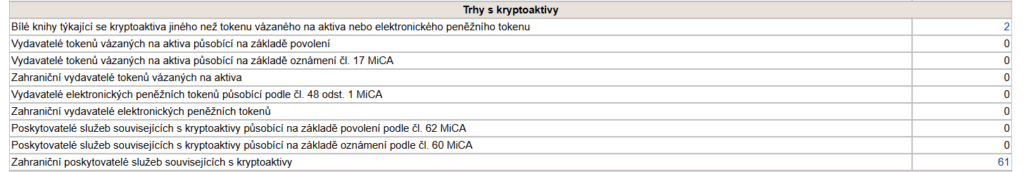

If you look at the CNB register (JERRS) today, 8 January 2026, you will see what I am attaching – a big zero:

As of today, the number of applications received has certainly increased slightly, so we are at approximately 250 applications. When considering the probable scenario in the Czech Republic, the following facts (as of 31 October 2025) are important:

- Number of discontinued proceedings: 81 proceedings were discontinued (34.3% of the total)

- Number of suspended proceedings: 213 proceedings were suspended at least once (90.3% of the total)

- Non-compliance with form of submission: 13 cases where applicants did not submit the application in the correct form according to Section 37(4) of the Administrative Procedure Code (for example an email without electronic signature, which was not supplemented within 5 days)

The figure for proceedings suspended at least once is misleading because proceedings may be suspended merely due to a request to pay an administrative fee. It is therefore unfortunate that we do not yet know in how many cases there has been repeated suspension or suspension for other reasons. Nevertheless, it can be expected that in the vast majority of cases, the CNB will say „no“. By the end of October, it had already done so for 94 applicants (81 discontinued cases + 13 cases of non-compliance with form), which meant that approximately 41% of all applications did not pass through the CNB as of that date.

Why Is This Happening?

We must realize that we have a kind of procedural premiere here. The CNB must this time comply with clear procedural rules for deadlines. With other types of licensing proceedings, it was not surprising that licensing procedures lasted for years, i.e., repeated bilateral communication took place, where the applicant could, in coordination with the CNB, supplement new documents or correct already submitted documents. This is not possible this time.

According to the MiCA Regulation, the CNB has short deadlines for assessing applications: 25 working days to check completeness and another 40 working days to issue a decision (approximately 3 months in total). This is significantly shorter than for other financial institutions.

In practice, however, the regulator almost always requires further clarifications and evidence. But how does the CNB handle requests for clarifications and further evidence in MiCA applications? In such a way that it constitutes either incompleteness or incorrectness, thus leading to the discontinuation of proceedings in light of the clearly established procedural deadlines under MiCA?

I note that the discontinuation of proceedings is not the same as a decision to reject the application. Proceedings are discontinued, for example, when the applicant fails to remedy deficiencies upon request. However, the outcome for the applicant is effectively the same. As is evident, the CNB chooses the path of discontinuing proceedings, and it can be legitimately assumed that this is precisely with reference to the above-mentioned procedural rules of MiCA.

Possible Scenarios

Pessimistic scenario: Of the 236 applications, only 30-50 entities (13-21%) will obtain a license by 1 July 2026. Most applicants will not be able to supplement the required documentation in time or will not meet capital and compliance requirements. Many smaller providers will cease operations.

Optimistic scenario: The CNB will accelerate processing during the first half of 2026 and issue 80-120 licenses (34-51%) by the end of the transitional period. Some applicants who have suspended proceedings will successfully supplement their documentation.

Realistic scenario: By 1 July 2026, approximately 50-80 Czech CASPs (21-34%) will have a license, while the remaining 40-60 foreign providers will operate in the Czech Republic through passporting.

My assessment? Since the CNB always has a large number of requirements, we must stick to the lower bound of the most pessimistic scenario. That is, a maximum of 13% of all applications, which out of a total of approximately 250 applications could mean perhaps only around 30 entities. Nevertheless, I believe the AI prediction was too optimistic, and it would not be surprising if the results would be even worse.

European Context

ESMA issued a peer review report in July 2025 with recommendations for all national regulators to pay particular attention to areas such as business growth, conflicts of interest, governance, and intragroup arrangements when assessing applications. This indicates that standards will be strict across the entire EU (ESMA Recommendations).

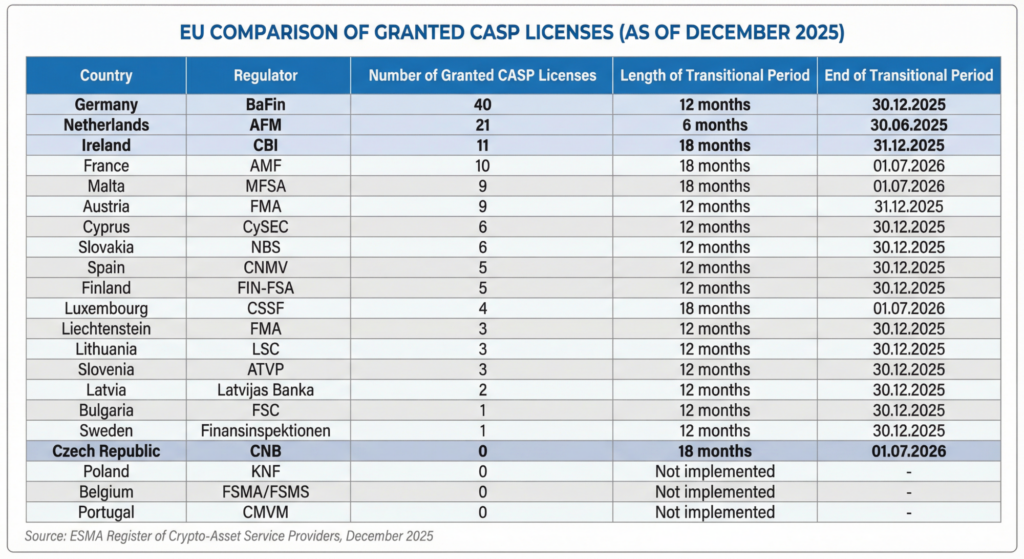

But what is the reality of comparing the Czech regulator with others? It reflects the enormous strictness of the CNB:

The first (originally) Czech company that has already obtained a MiCA license preferred to turn to another regulator. The company Confirmo (founded in 2014 in the Czech Republic) obtained a license from the Central Bank of Ireland in December 2025 (E15 Article). This case illustrates the strategy of some Czech companies that prefer licensing abroad (so-called „regulatory shopping“) rather than waiting for the lengthy process at the CNB.

This explains why 61 foreign providers appear in the Czech JERRS register. However, providing cross-border services during the transitional period is complicated. ESMA, in its statement of 17 December 2024, pointed out that different transitional periods should be taken into account (Moderní Právník Analysis).Essentially, this means that the shorter transitional period takes precedence – and the Czech Republic happens to be among the countries with the longest transitional period (18 months)! So if a Czech CASP (with a transitional period until 1 July 2026) wants to provide services in the Netherlands (where the period ended on 30 June 2025), it would need either a Dutch license or a full MiCA authorization.

You may have noticed that the Czech Cryptocurrency Association recently congratulated its first member on obtaining a license. This is Bitcoinmat.org, but unfortunately the CNB cannot claim this first success either, as the license was granted by the Slovak regulator.

EU Comparison: How Does the CNB Measure Up? Czech results significantly lag behind. According to the official ESMA register, as of December 2025, a total of 139 crypto-asset service providers (CASPs) were authorized in the European Union across 17 jurisdictions (ESMA Register):

I would also like to note that Ireland, Germany, and France provide extensive guidance materials, FAQs, sample forms, and pre-application consultations for applicants. I myself found such practical guides on the German regulator’s website that I did not find elsewhere. For example, the Irish Central Bank published a detailed CASP Application Form and Anti-Money Laundering Pre-Authorisation Risk Evaluation Questionnaire. This certainly significantly improves the quality of submitted applications.

Conclusion

I can only conclude the situation in the Czech Republic by saying that with zero licenses granted as of 8 January 2026 and only 6 months remaining until the end of the transitional period, the situation is unfavorable.

While leading jurisdictions such as Germany (40 licenses), the Netherlands (21 licenses), and Ireland (11 licenses) have already built functional licensing systems and attracted international players, in the Czech Republic it appears to be a combination of:

- Inadequately prepared applicants

- Possibly limited regulatory capacity

- The aforementioned fact that the CNB may approach even the smallest requirements formalistically – that is, in the MiCA regime, through simple discontinuation of proceedings instead of further cooperation with the applicant

For full objectivity, I add that it is evident that many applicants in the Czech Republic primarily wanted to submit an application by 31 July 2025 in order to utilize the transitional period. However, this clearly manifested itself in very low quality of applications (see also Seznam Zprávy Analysis).

The comparison with other EU countries also shows enormous fragmentation in the speed and approach to implementation – from the Dutch 6 months to the Czech 18 months of transitional period, and from German 40 licenses to Czech or Polish zero. We can hope that from 1 July 2026 the situation will become significantly clearer; for now, I predict only a few large players capable of meeting the strict requirements of the CNB.